5 Top Tech Solutions For Hybrid Companies

With over 50% of US workers working remotely at least once a week and tech solutions catching up quickly to meet the new challenges faced by modern businesses, hybrid workplaces... Read More

6 ways to save $$$ on your office space.

Learn more >April 23, 2021 | by

There has been a lot of speculation about the changes in work that will result from COVID and the “Work from Home” experiment. Lots of people seem to be converging on the idea that the five-day, 40-hour office work week will be a casualty of COVID.

Quite a few people also seem to think that the resulting anthropological change in work behavior will cause people–who have enjoyed no commute and greater flexibility and more time with their family–to request or require the ability to work from home some significant percentage of their time. A report from the Pew Research Center from December 2020, using a stratified random sample of around 6,000 people came up with the remarkable data that “54% say that, if they had a choice, they’d want to work from home all or most of the time when the coronavirus outbreak is over.” McKinsey studied interaction data among many job classifications and concluded that 20-25% of all workers could WFH three to five days per week, an increase of four to five times over pre-pandemic levels.

The idea that seems to occur perhaps most often is that people will go back to work with three days in the office and two days at home. This seems extremely logical and is going to be hard to argue until we have more data about how people react when some significant group of employees chooses to work in the office all (or almost all) the time, and another group works at home two or three days per week. Let’s assume for the moment that the change described is permanent.

The next topic found in many articles and blog posts is that this reduction of 40% in the number of days in the office will translate certerus paribus into a reduction in office demand of roughly the same amount. “Why,” asks the CFO or CEO, “would I want to pay for expensive office space when my people are working from home three days per week?” And this question is logical when put that way and by the C-suite, which frequently regards office space as excessively expensive; this is a trend that has been going on for decades.

The problem is that people don’t use office space like they use copier paper. And the path to reducing office space has to run through the step function that is office space utilization.

When people “consume” office space, that generally means that they have a fixed position in the office that they go to each day. The size of this position varies, ranging from hierarchical organizations with progressively larger space standards for those higher up in the organization (which was the vast majority of organizations ten years ago) to more “modern” or “egalitarian” organizations that might flatten the hierarchy and give everyone or almost everyone the same space allocation. But in general, both of these methods give each employee a place to come to when they enter the office, not 60% of a space.

Now some reading this might say, “What about hoteling or hot-desking?” or the variations in which individuals do not have fixed positions but use some method to schedule their place when they need to be in the office. The issue of whether these methods are an effective way to organize work has been the subject of a great deal of business, architectural, and academic debate that began in the 1990s and continues to today, and is beyond the scope of this piece. What I would like to engage with are these issues:

Managing a complex enterprise is, well, complex. Perhaps the most challenging aspect is the job of meshing personalities and project goals. To accomplish this, a manager or an executive has many tools. One of those tools is requiring that their people are in a specific place at a specific time. Taking that away by allowing staff to determine when they are going to be in the office or at home makes that much more challenging. While we have “proof of concept” on the viability of working from home, that knowledge only applies when everyone is working from home. The same Pew Research post mentioned above also points out that 47% of people in a supervisory role feel “worn out” by Zoom calls. This research was published in December, and this fatigue level is probably higher today.

Managing a team or department whose physical presence will be continually shifting is not tested, and seems rife with complications. For example, let’s assume that Sarah is giving a presentation at a staff meeting on Friday to six of her colleagues. But Friday is Sarah’s WFH day. She can certainly do the presentation over Zoom, but with her six colleagues all in the office it would really be preferable to have her up front, reading the room, and available at the end in the hallway to chat with her team as they walk to their desks. So her Manager suggests she come in Friday. But this conflicts with plans Sarah has made, and by the end of the conversation, both parties feel bad. If everyone was on Zoom this wouldn’t even have come up, but everyone (Sarah included) knows that the staff meeting will be better in person, for collaboration, for team building, and for idea generation.

This is just one example of the managerial juggling that will take place in the new post-COVID, hybrid world. How would space play into this? Assume that the company had reduced its space by 40%. After the tough conversation with her boss Beth, Sarah moves things around in her life and frees up Friday. Beth is pleased and goes to the corporate reservation system and finds that there aren’t enough seats for Sarah and the rest of the team. So Beth starts sending Slack messages to other managers to see if they can have people not come in on Friday to free up spots. And so the unhappy conversations spread out in waves through the organization. Beth wonders to herself: “with all the challenges we have to overcome post-COVID, wouldn’t it have been better to just keep the space?” At least one dimension would have been fixed in place, and that would be a lot less expensive than losing Sarah with her seven years of experience!

Here are a couple of case studies that try to examine this from an organizational perspective:

Let’s start with the pre-COVID status quo. A company (ExCo) has a lease with several years left to go and is under a lot of expense pressure. They are therefore considering subleasing a significant portion of their space. ExCo has decided to allow all of its staff to work from home two days per week and would like everyone to be in the office three days per week. Like most companies, ExCo has assigned positions for their employees, including a few private offices, workstations, and some bench seating. In recent years they converted some fixed positions into collaborative space, keeping their footprint (square footage) the same by “densifying” some of the space through benching. The organization had studied and considered going “free address” through a hoteling plan, but because of employee pushback and management consensus, that plan had been shelved permanently.

ExCo is therefore a very typical American consumer of office space. So how does this WFH flexibility affect their use (demand for) space? Well, in order to reduce their space, it will be necessary to timeshare positions in the office: that is a given. But how to coordinate who comes in when? One approach would be to rotate by splitting the office into two groups A and B and have each group come in on alternating days. This presents many issues, but the first is that it doesn’t accomplish management’s goal of 60% of time in the office. One possible fix: ExCo sets up a three-day rotation. Initially Group A comes in M/Tu/W; Group B comes in Th/F/M. Next, Group A comes in Tu/W/Th and B comes F/M/Tu…and so on.

When this plan is proposed, everyone agrees: this is unworkable. How can staff plan their home-work around such a variable schedule? And management looks at the actual work performed by ExCo and notes two things: first, most work is done by cross-departmental teams and second those teams change staff fairly often as work evolves. Also, departments like to have staff meetings to determine if the department is hitting its overall goals, and everyone agrees these meetings are best done in person. If A and B are chosen by department, then scheduling the teams becomes challenging; if by team, then the departmental interaction can’t be easily done in the office. How can the simple-sounding 50-50 division actually get accomplished?

The CEO suggests that ExCo can just rebalance the groupings as time goes along, and the department heads all look at each other and roll their eyes. Does the CEO understand what is entailed with the HR problems this will produce? Or the failure to genuinely provide flexibility to the team when the WFH days are set so rigidly–this was supposed to make things better, not just more complicated!

A second method for sharing space would involve a decision that all “flexible” workers would give up assigned positions and would simply sign up for spaces on an as-needed basis. ExCo would state an expectation that staff go to the office some mandated number of days, but wouldn’t attempt to define anyone’s schedule. A reservation system would be built or purchased to allow sign-up.

In parallel to this, the company would downsize its space to save money. Since there would be no overarching design for attendance beyond the “3-day rule” or whatever was chosen, it would not be possible to assign permanent positions seats and so some form of “hot-desking” would be requisite. So departmental location, personal items, and place-related status would all need to be eliminated, or at least reconsidered.

The question here is: how much space reduction would be practical under this policy? The main issue is that any plan must accommodate the worst-case scenario as well as the expected case. What are these?

The expected case is pretty simple and is what most authors seem to assume when considering this issue. If, say, everyone is at work three days per week, then the expected occupancy on any day would be 60%, and planning for that would suggest that space could be reduced by (approximately) 40%.

People writing about dramatic changes in office demand and therefore office building values seem to be thinking this might occur. But is this realistic? If people rely on their own scheduling, without a holistic plan, it would be likely that their desire to be in the office would be basically uniformly distributed across the middle of the week (Tu/W/Th), with perhaps a significant reduction in desire to be in the office on Monday and Friday. How much less? There have been studies about attendance for different weekdays, and there is perhaps less variance than one might expect.

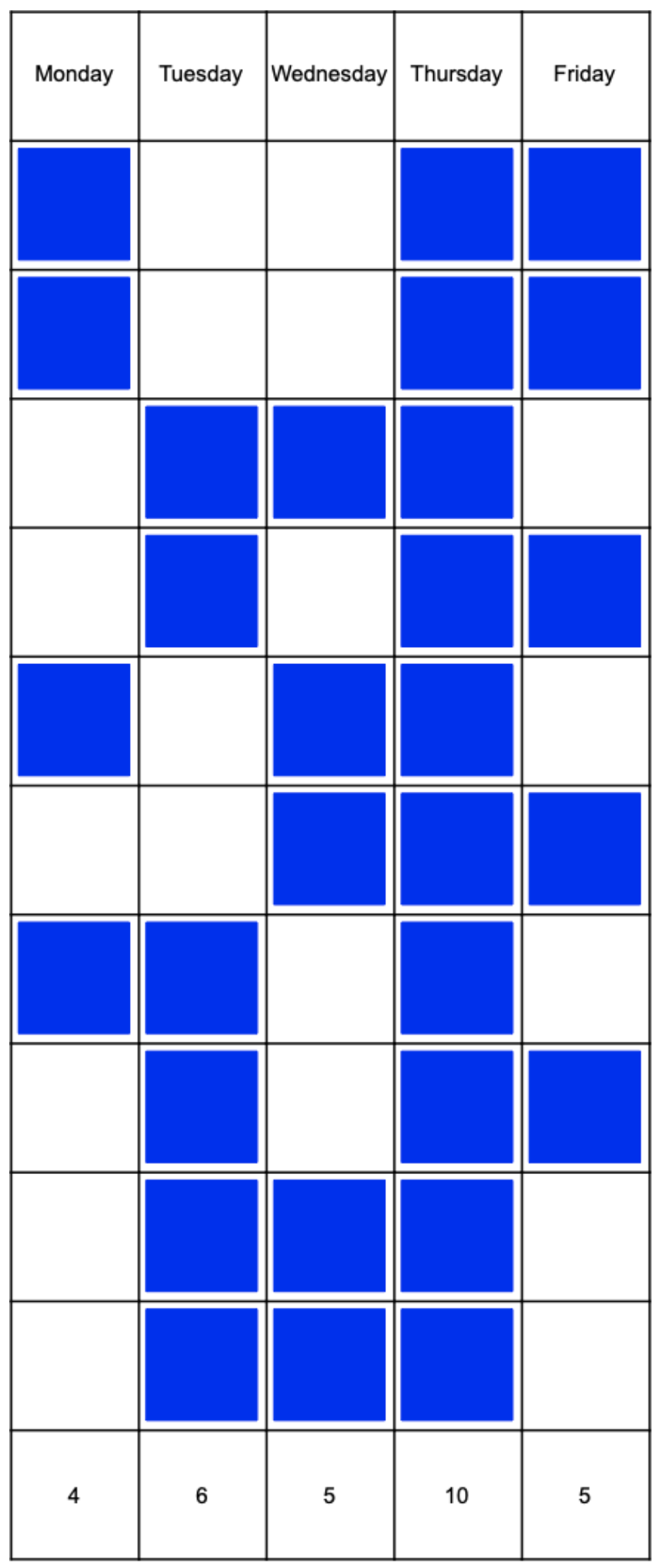

Assuming that demand for each of the days for working from home (and the inverse) would look something like this, with the numbers representing the percentage of the week that each day would represent as a desired day to be in the office.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 18% | 22% | 22% | 22% | 16% |

It’s clear that this will create clustering of demand for a place on those middle weekdays, and the randomness generated by allowing people to choose their own schedule would exacerbate this clustering. How can we assess the worst case? One approach would be to assume that the schedule is a random variable distributed as above and then run a simulation to examine the capacity required to meet the demand for each day of the week over many simulated weeks. The goal of the simulation is to see how many days of the week would be above any given level of provided spaces.

One way to visualize this is the following graphic, which shows how people would come in on one simulated workweek.

In this hypothetical week, Monday would be under-capacity, with 40% on Monday and 50% on Wednesday and Friday. Tuesday would be “just right” at the expected level. But Thursday would be significantly oversubscribed, and would present a management challenge, since employees who–either for personal or organizational reasons–needed to be in on an oversubscribed day and unable to find a seat would, we assume, express their unhappiness to management. The fundamental problem is that without completely controlling the nature of work, it’s difficult to completely control the place in which work needs to be done.

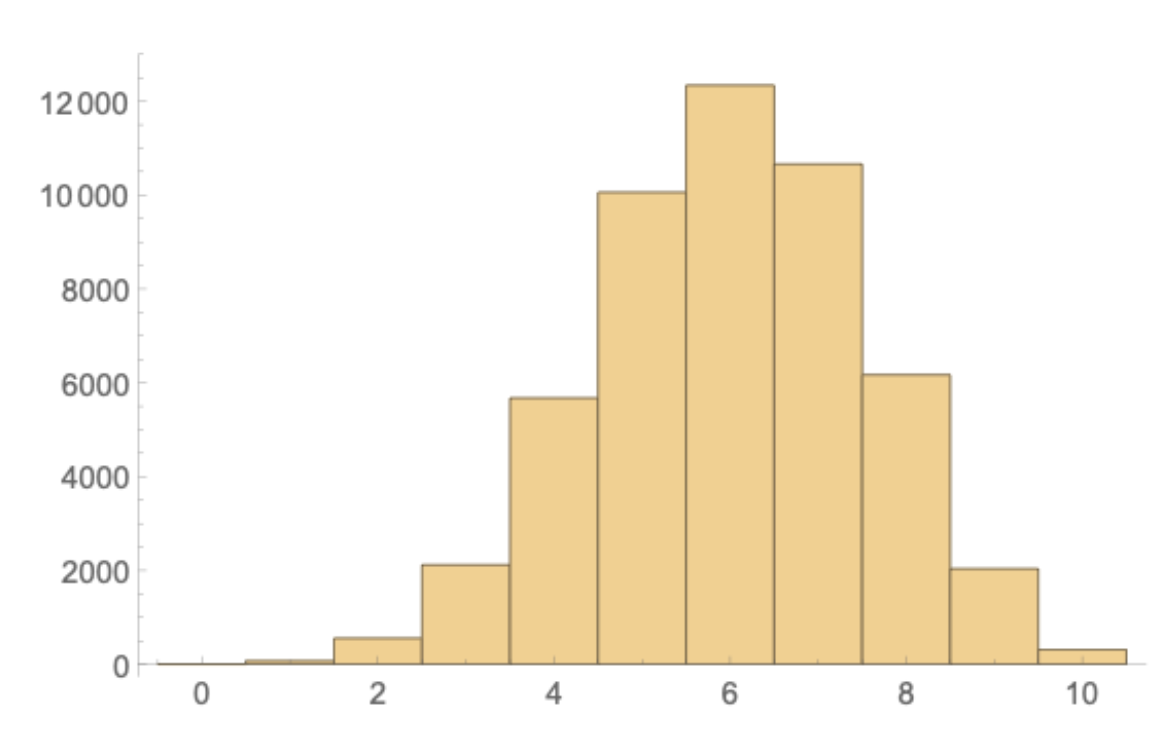

Running this simulation many times can be used to produce a histogram of the number of times in which people would want to show up in the office. For simplicity, this is done on a scale of one to ten. This makes it easy to compute the percentages. As you would expect, the most likely number would be six:

However, a significant number of days would be oversubscribed with seven and eight being very popular outcomes as well!

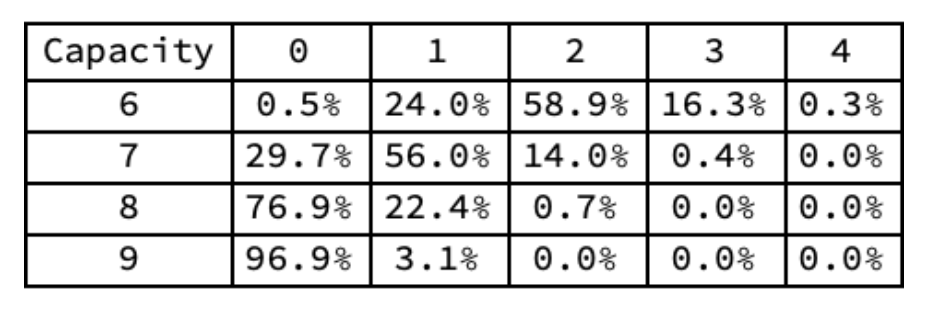

As an experiment, let’s look at a series of simulated weeks, counting the total number of required seats and relating that to different levels of capacity. The top row illustrates over-subscription by 0,1,2,3, or 4 spots, and the first column represents a nominal number of seats. The percentages show how frequent the different capacities get overloaded at least once per week:

What this shows is that providing nine positions essentially eliminates the problem of oversubscription, as you might expect. However, providing six in the simulation gives the result that you will have at least one more person than position almost every week. Going to eight positions leaves you with around 22% of the days oversubscribed by one, which seems much more manageable.

This analysis does not take into account the calendar, which would tend to make certain days less popular for in-office work—for example, before and after holidays, very bad or very good weather, etc.—all of which would tend to cluster demand for in-office days. This would make the problem worse. On the other side of the ledger, the analysis doesn’t account for travel days, vacation days, or other days that would reduce crowding.

One conclusion that seems to stem from these simulations is that having more than the “expected value” number of positions would provide a much-needed safety margin against overcrowding and organizational disruption. It should be noted in passing that office occupancy has traditionally averaged significantly less than 100% but despite this, corporations have not successfully reduced their footprint to match the less-than-100% occupancy level, probably for the same reasons described prospectively here.

Framed in this fashion, the trade-off is “worst case” demand and the attendant organizational and HR issues, versus real estate cost savings. The anthropological changes needed to hot desk or hotel all or a large part of the company are hard to quantify but have some cost as well (or all companies would have implemented them in the past). Each organization will evaluate the tradeoff differently and current economic conditions might make the expense savings seem more attractive as organizations struggle with reduced revenues in the wake of the pandemic. However, it seems likely that some compromise position would be arrived at by most executives, particularly because human capital costs around 7-10 times real estate, and an unhappy employee is a direct path to turnover.

For the author, keeping 90% of the prior capacity and mitigating virtually all of the overload days would make good sense. At between $5,000 and $10,000 annually for real estate costs ($50 psf X 150 sf = $7,500), this seems like a good insurance policy against declines in morale, productivity, retention, and ultimately revenue. It is important to note that this analysis is really about a lower bound for space availability, rather than a one-size-fits-all solution for all spaces. It is likely that some parts of the organization will function best at the same (roughly) 1-1 ratio of spaces to employees that was the pre-COVID norm. Other positions seem logical as well, but the simplistic “3 days = 60% of the space” does not.

Additional sources consulted

SquareFoot is a new kind of commercial real estate company. Our easy-to-use technology and responsive team of real estate professionals delivers the most transparent, flexible experience in the market. Get in touch to start your search today.